Bureaucratic silliness in Brazil that weakens the Portuguese language (plus: the status of English in the United States)

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

Over on Auxlang today we got into the discussion on making English the de jure official language of the United States, and whether that would be good for the country as a whole, the role of an auxlang in the world and whether it would result in more going back and forth across borders due to the increased ease, or whether it might result in less as a result of not having to travel to other countries to learn their languages and placing nations on a linguistically equal footing. In the midst of this Antonielly Garcia Rodrigues added this interesting post on some real bureaucratic silliness in Brazil and Portugal (actually I'm not sure if Portugal does the same but I wouldn't be surprised) where the two pretend not to understand perfectly legible Portuguese until it is 'translated' into their own written standard.

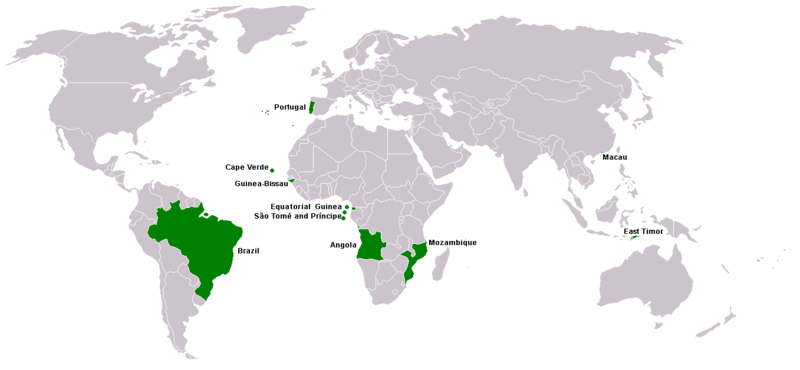

And considering their huge population, Brazil can't pretend that its variant of Portuguese is anywhere close to being in danger. IMO this does nothing but weaken Portugese as a language on the world stage. What of poor East Timor when it communicates with Brazilian diplomats, will there have to be 'translations' of the documents used there too?

Here's the post written by Antonielly. Don't forget that it starts out talking about English in the United States:

I fail to see what people would gain if the government adopts it as a de jure official language. It is already the de facto official language; it is used by governmental services, by Justice, on education, and by mainstream media. This use will not change, and rightly so.

Since its effects would in practice be just symbolic, I just see an official "English-only" law being misused (on the streets, not at tribunals) by laypeople to be more openly hostile to immigrants, to Americans who are bilingual due to their families (e.g. many

Sino-Americans), and to Amerindians.

Brazil has a dumb law that regulates spelling. It is ridiculous because it adds more red tape to the system; for instance, if there is some reason the Ministry of Education should require some changes (or more flexibility) in the spelling system to be adopted by didactic books, it cannot do so; it has to request to the National Congress to pass a law to change spelling (e.g. to make it a bit more flexible). This would take a lot of time, since the National Congress has many other law projects competing for attention and spelling change is (rightly so) a low-priority one. In addition, discussing and voting a new spelling law would take time away from very important issues, such

as discussing and voting laws to improve economy, to free more money to the educational system or to better enforce human rights. It is clear that the spelling system(s) accepted for official use should not be something frozen by a law, but by joint decrees from the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Justice.

An example of change that cannot be done: The government cannot accept European Portuguese and African literature books at public schools if they are Portuguese editions, because the books that are edited in Portugal are written in the spelling adopted by Portugal (which is almost the same as the spelling adopted by Brazil, but not the same in a few words, something that does not harm mutual readability). Because of the dumb law, the Ministry of Education is not free to say that it

will accept books written in both spellings (but adopt the Brazilian spelling for teaching). So, a book written in European Portuguese can only be adopted by public Brazilian schools when it is "transliterated" to the Brazilian spelling, thus causing a distortion in the international lusophone publishing market and in the educational system. And international agreements by Brazil and Portugal (e.g. in the context of the CPLP [Lusophony]) have always to be "transliterated" to both spelling systems, thus spending valuable public money with "translators" in a silly bureaucratic activity.

4 comments:

It is also worth adding that in 1990 Brazil and Portugal made an agreement to reform spelling in both sides of the Atlantic:

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acordo_Ortogr%C3%A1fico_de_1990 The agreement was signed by the presidents and approved by the parliaments, however the spelling reform hasn't happened yet.

Both countries promise to start enforcing the agreement in a few months. This would reduce some of this silly bureaucracy for the time being.

However, even if this happens, the main problem will not be solved: future official spelling changes will still require approval by the parliament. The scenario of an independent spelling change of 10 frequently used words in Angola and Mozambique, for instance, would render African literature inaccessible in Brazilian schools even if it didn't harm readability. And the government would not have the authority to readily accept that literature in public schools because the new African spelling would be against the law imposed by the parliament. That is simply ridiculous.

Considering that international relations are not very stable, I would not be surprised if in the next decades there were another bureaucratic drama due to the need of reupdating spelling or of accepting modest variations that emerged in other lusophone countries.

Oh, and in Portugal it is the same silliness. Spelling changes or acceptance of other spelling systems (even with the status of read-only) would require parliament approval as well.

I wouldn't be surprised if the same stupidity ocurred in La Francophonie space. Regulating language by law (instead of by custom) does more harm than good.

Hot news: Portugal has just officialized the 1990's agreement. Now spelling will be changed across the whole CPLP space.

http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/folha/educacao/ult305u424534.shtml

It is also worth adding that in 1990 Brazil and Portugal made an agreement to reform spelling in both sides of the Atlantic:

http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acordo_Ortogr%C3%A1fico_de_1990 The agreement was signed by the presidents and approved by the parliaments, however the spelling reform hasn't happened yet.

Both countries promise to start enforcing the agreement in a few months. This would reduce some of this silly bureaucracy for the time being.

However, even if this happens, the main problem will not be solved: future official spelling changes will still require approval by the parliament. The scenario of an independent spelling change of 10 frequently used words in Angola and Mozambique, for instance, would render African literature inaccessible in Brazilian schools even if it didn't harm readability. And the government would not have the authority to readily accept that literature in public schools because the new African spelling would be against the law imposed by the parliament. That is simply ridiculous.

Considering that international relations are not very stable, I would not be surprised if in the next decades there were another bureaucratic drama due to the need of reupdating spelling or of accepting modest variations that emerged in other lusophone countries.

Post a Comment